WHO HASN’T ENCOUNTERED RAVEL’S MUSIC?

Chances are you recognise at least a snippet of the world-famous Boléro, even if you can’t quite recall where from or associate it with a title or composer – such is its ubiquity in everyday life. The great irony is that Ravel’s most celebrated piece is also one of the most singular in his entire catalogue – above all, an orchestration exercise – that in no way represents the broader musical world of its creator. On this 150th anniversary of Ravel’s birth, we invite audiences to immerse themselves in some of the most enchanting corners of the unique, personal, and utterly irresistible universe he left us.

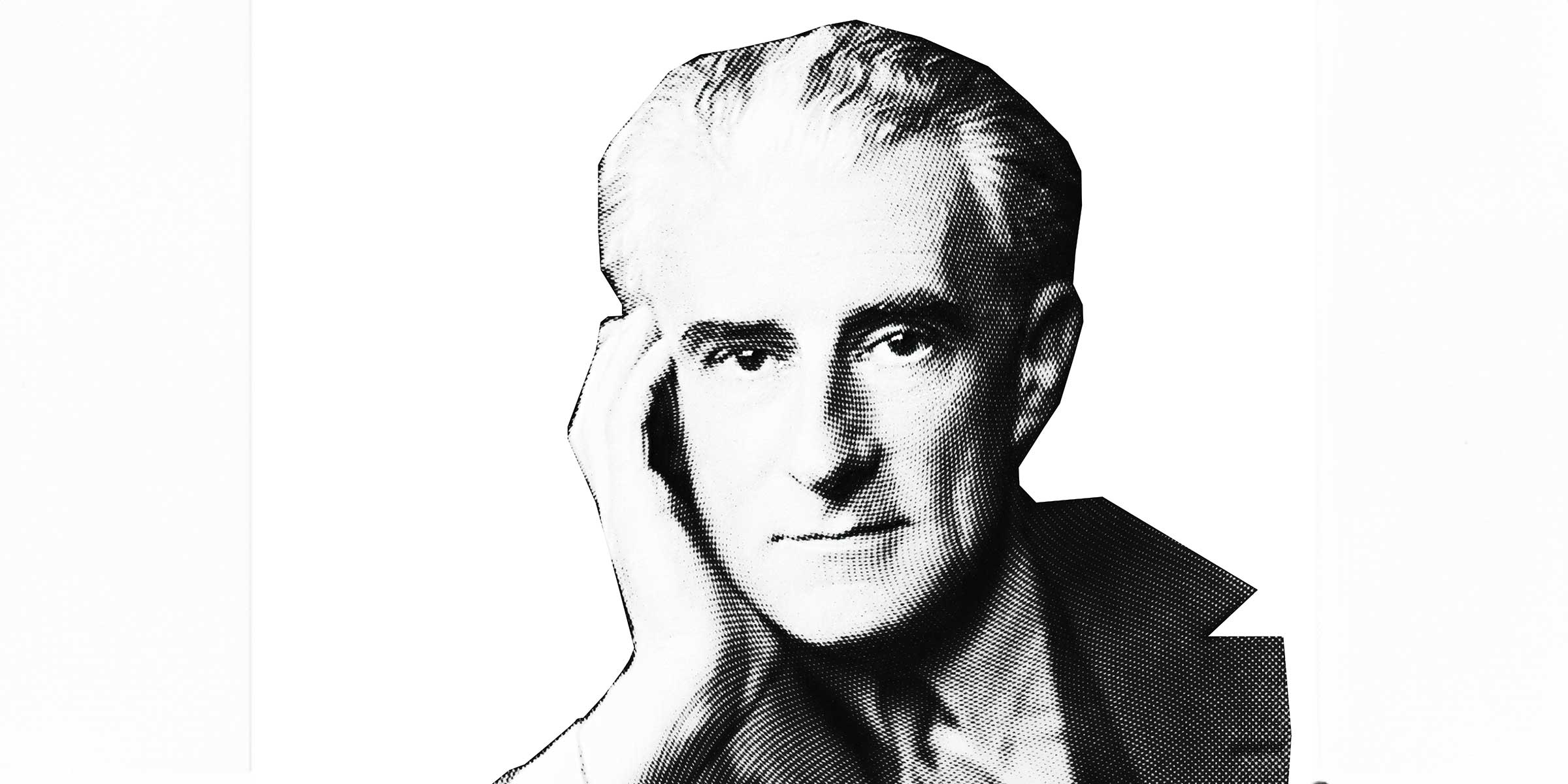

Born in the Basque region of southwestern France, Maurice Ravel (1875–1937) was the most prominent French composer of his generation, a contemporary of revolutionaries such as Schönberg and Stravinsky. In simplified narratives of music history, he is often mentioned alongside Debussy as a prime example of socalled Impressionist music. Yet Ravel’s artistic profile is unusually eclectic, drawing from a vast array of influences while maintaining a sound world of immaculate polish and unerring elegance.

Of course, there are undeniable links to Impressionism. The same dreamlike appeal, the sensory allure, the imagery of water, the almost visual quality and poetic suggestion – these all flow through works such as Gaspard de la Nuit for piano, the groundbreaking Jeux d’Eau (from 1901, predating Debussy’s “watery” pieces), Une Barque sur l’Océan (in both its piano and orchestral versions), and of the ballet Daphnis et Chloé. Ravel’s fascination with music from distant cultures surfaces throughout his works, from the Eastern sonorities permeating the enchanting fairytale ballet Ma Mère l’Oye, to the blues influences in his Violin Sonata No. 2, or the jazz-inflected harmonies of his Piano Concerto in G and Concerto for the Left Hand. He also drew from Eastern European traditions (Tzigane for violin and piano, best known in its orchestral version), while Spanish elements – so cherished by Debussy – hold an even stronger presence in Ravel’s output, exemplified not only by Boléro but also Rapsodie Espagnole and the extraordinary Alborada del Gracioso (originally for piano but more widely known in its orchestral version, where it achieves a striking evocation of flamenco vocal style through instrumental means).

These influences coexist effortlessly in Ravel’s music, without conflict or contradiction. His admiration for past musical traditions aligns him with the neoclassical trends emerging in his time, seen in his homage to the French harpsichord school of the 18th century in Le Tombeau de Couperin, or the Renaissance-inspired Pavane pour une Infante Défunte. Yet this reverence for the past never prevented him from embracing the most avant-garde currents of his era – one need only listen to the astonishing Frontispice (1918) for two pianos and five hands (!), or the remarkable Chansons Madécasses.

As a form of sincere, free, and inspired art, Ravel’s music has captivated discerning listeners across generations, igniting imaginations in every sphere – from leading figures of his own time, like Stravinsky, to contemporary musicians such as the versatile Portuguese pianist Mário Laginha.

What better way to celebrate this master craftsman of sound than by experiencing one of his gems live? Join us at Casa da Música on 07 February, 14 March, and 16 March.

Joyeux anniversaire!